When I study nature, I love to learn about the superlatives. I appreciate how the tallest mountains, the biggest trees, or the oldest animals have a way to serve as ambassadors, helping people to appreciate the natural world even if they don’t understand the “nitty-gritty” science of everything. It’s with this mindset that I set off onto an interesting study of the huge role beavers play in the BWCA. One of my favorite places in the whole wide world is the BWCA. In my time guiding and taking personal trips, I am consistently looking for new lenses through which to appreciate it and, in turn, help others to love it more too. And beavers are a huge part of the BWCA being the way it is today.

In my study, I primarily set out with two goals:

“What does the impact of beavers look like on a landscape level?”

and “What are beavers capable of building? How big can they build?”

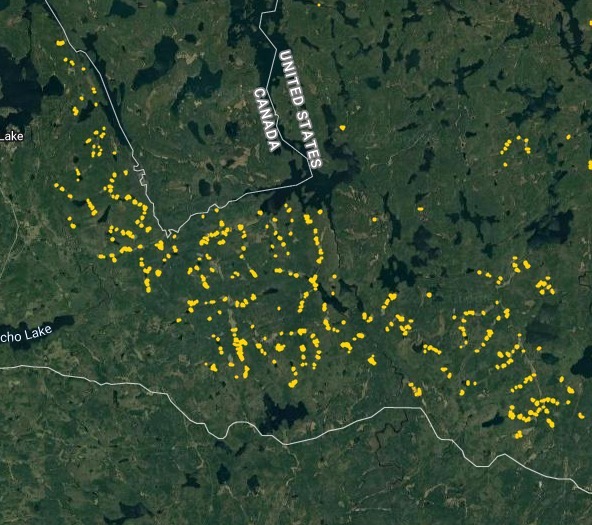

To answer the first question, I needed to choose a study area. I wasn’t going to map EVERY beaver dam in the BWCA, but I needed to map a big enough area to lend perspective. Since this was about the superlative, I also wanted to choose an area with a large beaver population which has been sustained over time. The best I could think of was the very western end. With an intricate network of rivers, streams, and marshes, it’s sort of the perfect beaver habitat. I ended up essentially mapping every beaver dam from Meander Creek to Crane Lake inside of the BWCA border (and including waters which flow into the BW.) I was only mapping dams which were easily discernible on the air photos (about 30 ft long and longer) and this yielded nearly 800 beaver dams in my 42,000 acre study area! Check out the map here.

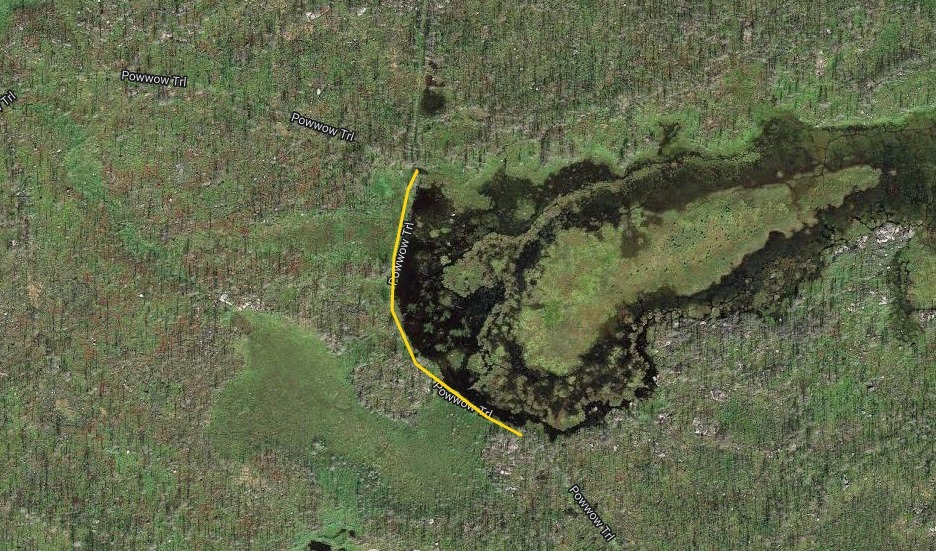

Beyond this, I also wanted to study how large of dams beavers could build and how long those dams last. Incredible articles like this one have described how beaver dams can lest centuries, even a millennia in one case. And this article connected to Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada claims the world’s longest beaver dam at 2542.65 ft long. With those stats in mind, I kept track of every beaver dam in three “large” sizes within my study area and then screened the rest of the BW for other superlatives (though my screening was far from in depth.) The three sizes noted in my data are 4-500 ft, 500-1000 ft, and long than 1000 ft in length. For any dams longer than 500 ft, I delved into a more detailed history including original construction date (if discernible), any notable additions, years of damage (or failure), years of replacement (if applicable), watershed, and an identification number to keep track of each individually. I used multiple historical air photo databases for discovering this data, but my air photos only go back to 1948 for this region. Also, as a bi-product of this study, I learned a lot about different shapes of beaver dams as well as individualism in styles and different beaver families’ preferences for redundancy (building lots of dams to catch every drop of water.) I also learned how to spot beaver dams based on characteristic shapes even more than a century after they were built.

Here are some highlights from the data:

I found evidence of approximately 15 different 1000+ ft dams in the study. Of these, two are “questionable” in terms of “is this whole thing a dam or is it multiple”? Once beaver dams reach the century+ mark, things become increasingly unclear as they essentially become land masses unto themselves with deep soil and trees. Of the 15 suspected 1000 fters, 8 were built before 1948 (and, in some cases, well before.) But some have been built this century already which blew my mind. How can beavers build something that is 1/5 of a mile long in 20 years? Of the less than 1000 fters, there were about 90 between 500-1000 ft and 60 between 400-500 ft. And the watersheds with the most beaver dams over 500 ft? Meander Creek, Nugget Creek, and Gaunt Creek. Probably not surprisingly, Nugget and Gaunt combine to become Beaver Stream which flows into the Loon River. I was blown away again and again by the beavers. Sometimes they built crazy interwoven dam structures which defy my understanding. Sometimes beavers returned 70 or 80 years later and either rebuilt an ancient dam or made a giant connector between old structures. It also seemed like certain beavers were masters at their craft while others were poor at best (and their creations lasted for a comparatively short time.) All in all, it’s incredible the level of impact the Beavers have had considering that, during the fur trade, this population would have been under a tremendous amount of pressure. They obviously have rebounded and what we see today is a very healthy beaver population in the BWCA.

Check out some examples and highlights below from the study.

Thanks for reading.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates about new articles, great deals, and information about the activities you love and the gear that makes them possible:

Have You Read Our Other Content?

Five Ways to Make the Most of BWCA Permit Day

With BWCA permit day just around the corner, plenty of people are waiting in eager anticipation of how opening day will set the trajectory of their summer trips. Some people will log on the moment that permits open to try to reserve a premium entry point on the dates that they are available to go.…

10 Steps in Planning an October Canoe Trip to the BWCA

Fall is a magical season in canoe country: a brief respite of quiet calm between the relative chaos of summer and the icy grip of winter. And, in many ways, the experience of a canoe trip in the BWCA is greatly enriched by the season. Once October 1st rolls around though, the looming threat of…

The Route Planning Game

“Probably the best remedy for the canoe freak is map watching. Pouring over maps can often get you through the canoeless season when nothing else can. I recommend it highly. If you coat the maps with plastic, you can even use them as tablecloths, curtains, and all sorts of things. However, no matter what you…

An Expert’s Perspective on BWCA Forests

Lee Frelich, Director of The University of Minnesota Center for Forest Ecology, is one of the foremost experts on the forests of the BWCAW and the fire ecology that dictates its composition. We interviewed him to gain his invaluable insight into this incredible ecosystem, its history, and a glimpse into its future. Question 1. For…

How to Hike the BWCA this Fall

For those of us whose Boundary Waters trips don’t end with canoe season, Fall can be a challenging time to decide what activities to pursue. As the ice begins to line the outer edges of the lakes and canoeing becomes tougher, it’s just the perfect time of the year to hit the trails and backpack…

Echoes of ’93 – Managing a Complicated Wilderness

“There is currently too much visitor use in some areas of the BWCAW on some days. Excessive use results in the following impacts: Off-site camping on non-designated sites which impacts vegetation, soils, and heritage resources. Some designated campsites and portages are too heavily impacted based upon our LAC inventory data. Approximately 85% of all existing…

Emergency Communication in the Wilderness – 4 Things To Know Before Your Canoe Trip

If you’ve never been on a wilderness trip before, the idea of traveling beyond cell service, seemingly out of touch with the rest of the world, can seem daunting. The questions are many: How do we let concerned family members know where we are? Will there be any cell service? What if we need to…

5 Guide Tricks for Finding Great BWCAW (or Quetico) Campsites

Finding a great campsite can be one of the great joys of a canoe trip. Waking up in a stand of majestic pines, enjoying a cool breeze rolling off the lake on a midsummer afternoon, and cooking over a campfire without worrying about bugs can make a campsite that much more memorable. Occasionally, these sites…

Is it Spring in Canoe Country Yet?

This winter has felt like a long one. The final weeks before opening water always do, but this year has felt extra drawn out. Numerous cities in Minnesota have broken their snowfall records and ice is still firmly on the lakes around Ely. To the Boundary Waters enthusiast, this is a painful time of year…