When I study nature, I love to learn about the superlatives. I appreciate how the tallest mountains, the biggest trees, or the oldest animals have a way to serve as ambassadors, helping people to appreciate the natural world even if they don’t understand the “nitty-gritty” science of everything. It’s with this mindset that I set off onto an interesting study of the huge role beavers play in the BWCA. One of my favorite places in the whole wide world is the BWCA. In my time guiding and taking personal trips, I am consistently looking for new lenses through which to appreciate it and, in turn, help others to love it more too. And beavers are a huge part of the BWCA being the way it is today.

In my study, I primarily set out with two goals:

“What does the impact of beavers look like on a landscape level?”

and “What are beavers capable of building? How big can they build?”

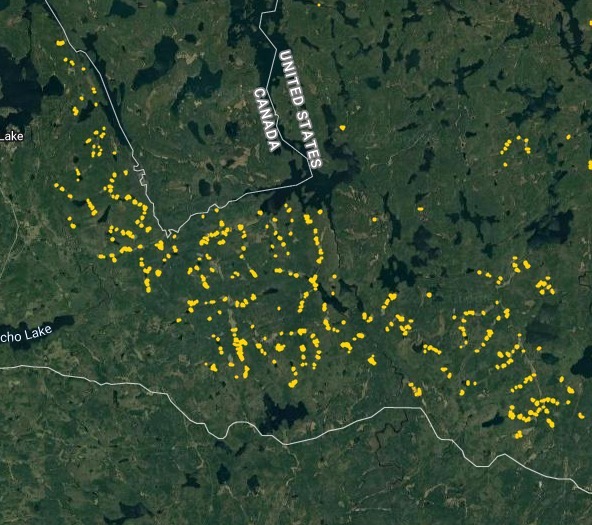

To answer the first question, I needed to choose a study area. I wasn’t going to map EVERY beaver dam in the BWCA, but I needed to map a big enough area to lend perspective. Since this was about the superlative, I also wanted to choose an area with a large beaver population which has been sustained over time. The best I could think of was the very western end. With an intricate network of rivers, streams, and marshes, it’s sort of the perfect beaver habitat. I ended up essentially mapping every beaver dam from Meander Creek to Crane Lake inside of the BWCA border (and including waters which flow into the BW.) I was only mapping dams which were easily discernible on the air photos (about 30 ft long and longer) and this yielded nearly 800 beaver dams in my 42,000 acre study area! Check out the map here.

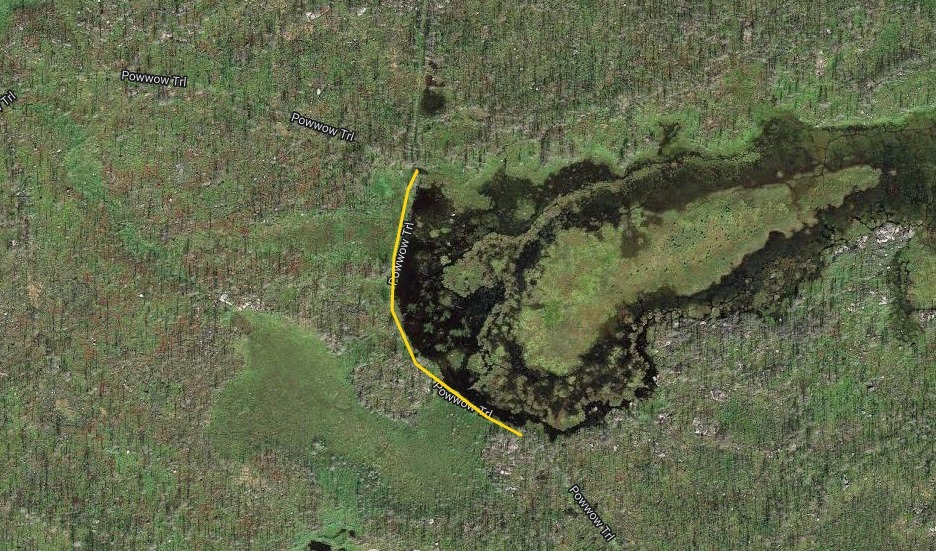

Beyond this, I also wanted to study how large of dams beavers could build and how long those dams last. Incredible articles like this one have described how beaver dams can lest centuries, even a millennia in one case. And this article connected to Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada claims the world’s longest beaver dam at 2542.65 ft long. With those stats in mind, I kept track of every beaver dam in three “large” sizes within my study area and then screened the rest of the BW for other superlatives (though my screening was far from in depth.) The three sizes noted in my data are 4-500 ft, 500-1000 ft, and long than 1000 ft in length. For any dams longer than 500 ft, I delved into a more detailed history including original construction date (if discernible), any notable additions, years of damage (or failure), years of replacement (if applicable), watershed, and an identification number to keep track of each individually. I used multiple historical air photo databases for discovering this data, but my air photos only go back to 1948 for this region. Also, as a bi-product of this study, I learned a lot about different shapes of beaver dams as well as individualism in styles and different beaver families’ preferences for redundancy (building lots of dams to catch every drop of water.) I also learned how to spot beaver dams based on characteristic shapes even more than a century after they were built.

Here are some highlights from the data:

I found evidence of approximately 15 different 1000+ ft dams in the study. Of these, two are “questionable” in terms of “is this whole thing a dam or is it multiple”? Once beaver dams reach the century+ mark, things become increasingly unclear as they essentially become land masses unto themselves with deep soil and trees. Of the 15 suspected 1000 fters, 8 were built before 1948 (and, in some cases, well before.) But some have been built this century already which blew my mind. How can beavers build something that is 1/5 of a mile long in 20 years? Of the less than 1000 fters, there were about 90 between 500-1000 ft and 60 between 400-500 ft. And the watersheds with the most beaver dams over 500 ft? Meander Creek, Nugget Creek, and Gaunt Creek. Probably not surprisingly, Nugget and Gaunt combine to become Beaver Stream which flows into the Loon River. I was blown away again and again by the beavers. Sometimes they built crazy interwoven dam structures which defy my understanding. Sometimes beavers returned 70 or 80 years later and either rebuilt an ancient dam or made a giant connector between old structures. It also seemed like certain beavers were masters at their craft while others were poor at best (and their creations lasted for a comparatively short time.) All in all, it’s incredible the level of impact the Beavers have had considering that, during the fur trade, this population would have been under a tremendous amount of pressure. They obviously have rebounded and what we see today is a very healthy beaver population in the BWCA.

Check out some examples and highlights below from the study.

Thanks for reading.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates about new articles, great deals, and information about the activities you love and the gear that makes them possible:

Have You Read Our Other Content?

10 Tips and Tricks for Nightime Canoe Travel

The vast majority of BWCA visitors paddle and hike during daylight hours and for good reason. It’s safer, there’s more to see, and daylight travel aligns with normal sleep cycles. Night travel, on the other hand, provides a higher risk of getting lost while paddling; it’s also easier to fall and get hurt while portaging.…

Six Rules for BWCAW Portage Etiquette

If you are new to wilderness canoe camping, especially in a heavily used wilderness area like the BWCAW, then the group traffic at some of the busier portages in Canoe Country may come as a shock. Here are six [written and unwritten] rules you should apply the next time you portage on a well-congested portage trail.…

How Trees Tell the Story of the BWCA

Today is the International Day of Forests which means it’s the perfect day to celebrate the trees of the BWCA. The Boundary Waters are a unique mosaic of forests born out of wildfire, windstorms, logging, and the passage of time. Despite the history of disturbance, the Boundary Waters contain the largest tracts of old growth…

Leave it to Beaver – How Beavers Change the BWCA

When I study nature, I love to learn about the superlatives. I appreciate how the tallest mountains, the biggest trees, or the oldest animals have a way to serve as ambassadors, helping people to appreciate the natural world even if they don’t understand the “nitty-gritty” science of everything. It’s with this mindset that I set…

How to Name Over 1000 Different Lakes: Part 2

Last year, we published an article about Boundary Waters lake names, their inspirations, their backgrounds, and which themes and names are common or often repeated. Among 1100 different lakes in the BWCAW alone, there are quite a variety of names! In this sequel article, we are visiting the BWCAW, Quetico, and Voyageurs National Park to…

The Route Planning Game

“Probably the best remedy for the canoe freak is map watching. Pouring over maps can often get you through the canoeless season when nothing else can. I recommend it highly. If you coat the maps with plastic, you can even use them as tablecloths, curtains, and all sorts of things. However, no matter what you…

A Fire Perspective: 200 Years of Wildfires

Few natural processes inspire the fear and awe that wildfires do. In nature, fire is a seeming paradox of death and new life. Gigantic, swirling infernos that engulf the landscape in an unheeding wall of flame become landscape-level scars healed by green shoots and wildflowers. And here on the southern edge of the boreal forest,…