What is the most difficult portage in the BWCA? This is an impossible question to answer. Is it the steepest? How about the longest? How about the one that has the most mud, the most bugs, the slipperiest rocks, or the worst landing? In truth, the most difficult portage is an entirely subjective question bent to the whims of the context in which you encounter it. An easy portage becomes treacherous in half a foot of snow and a portage that doesn’t challenge a young guide may overwhelm someone who is less physically able or is packed heavier. And just a short journey north to the Quetico or east to the Grand Portage may find larger challenges than can be encountered in the BWCA. But, for this article, I wanted to add one small measure of quantifiable to the otherwise subjective. And so, in the following graph and table, I compared side by side the steepest portages in the BWCA. Even what makes the steepest portage is a measure of some debate. For this article though, I used the total gain in elevation in feet, the number of rods traveled to get there, and the average slope over that distance. Most portages in the BWCA that gain considerable elevation lose some again as they come down to the next lake. In my chart below, I show only the distance utilized to achieve maximum height. The elevation gained may also have some measure of error. I used data from Paddle Planner for this study, and only really fact-checked for the very highest and the very steepest. Besides that, though the USGS data that most maps are based on has its merits, it’s a broad scale. Small yet dramatic changes in elevation are not noted so the handful of portages with true rock faces are not included. Many of the very shortest steep portages are also not included for this same reason. With that out of the way, I will explain some of the most noteworthy results below.

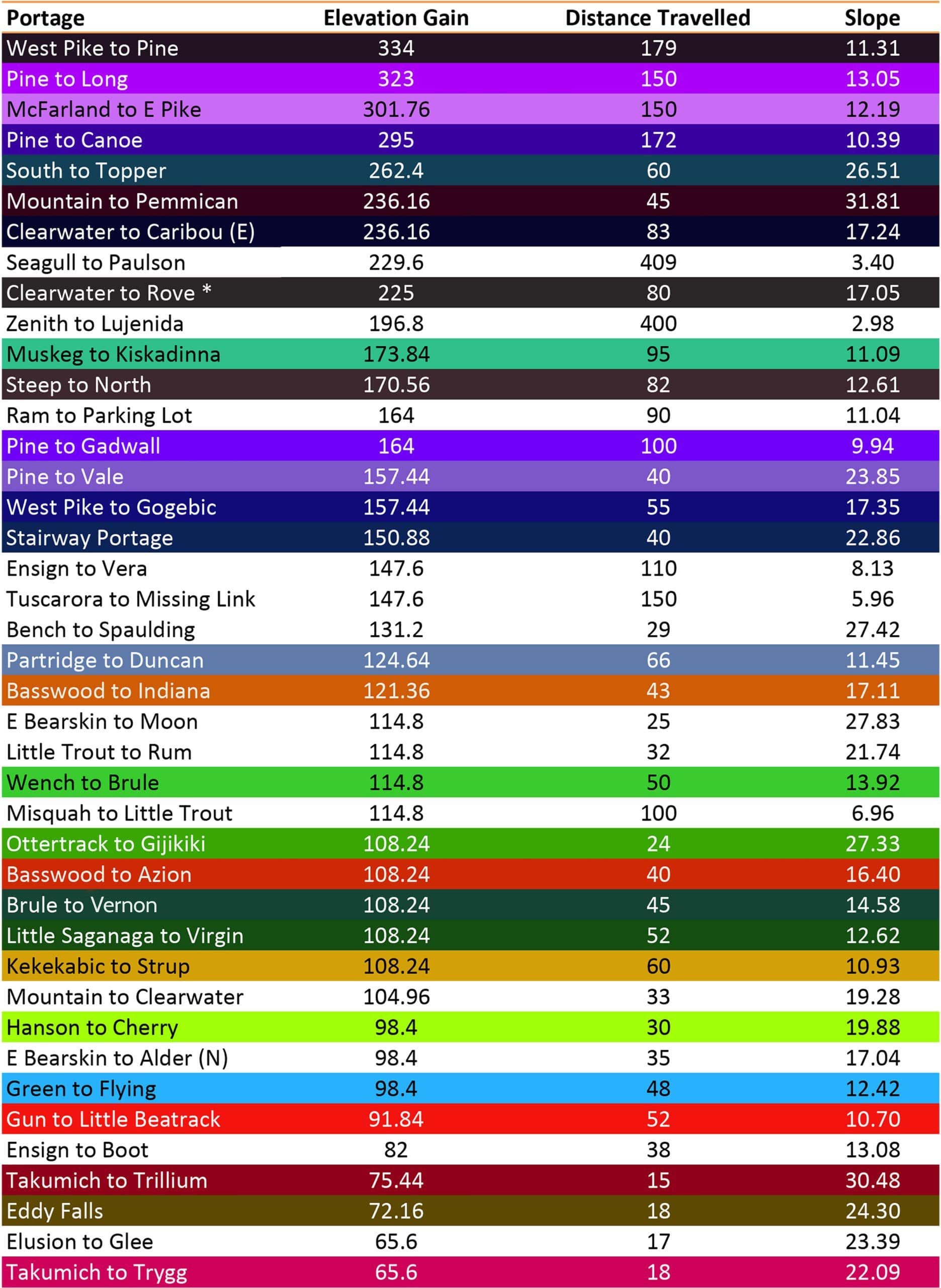

Some of the portages on this list are very famous (or infamous depending on your perspective.) Pine to Canoe (Johnson Falls), Stairway, Eddy Falls, and Gijikiki are just some of the names we have all told stories about, but how do they compare? Obviously, the Boundary Waters has zones where the portages are steeper. The area beneath Lac La Croix, the area between the north and south arms of Knife, the Misquah Hills, and the eastern Gunflint all come to mind. The area east of the Gunflint, to no surprise, sees far and away the greatest changes of elevation. Three portages in the BWCA exceed 300 ft of elevation. These all lay east of the Gunflint Trail and include West Pike to Pine, Pine to Long, and McFarland to E Pike. All three of these portages lay within a three-mile circle of each other with West Pike to Pine being the only regularly travelled trail. Pine to Long is a dead-end route with one campsite. McFarland to E Pike is likely not maintained anymore and is slightly overgrown as a result. All three of these portages, though gaining serious elevation, do so at a more prolonged distance. They each take over 150 rods to reach 300 ft of gain, steep for sure, but a shallower slope than others. In addition to three portages that exceed 300 ft of gain, six other portages (five official) gain more than 200 ft. All of these but one also lie east of the Gunflint Trail. Pine to Canoe (just west of the 300s), South to Topper, Mountain to Pemmican, Clearwater to Caribou (eastern portage), Seagull to Paulson, and Clearwater to Rove. Some of these portages are infamous for well-deserved reasons. Seagull to Paulson (a wonderous hike and terrible portage) spends a lot of time climbing up and down over bare rock in its nearly two-mile course. Pine to Canoe sits next to the trail to Johnson Falls. Clearwater to Caribou is a common route to get to Johnson. Others of these may be less well-known. Topper has an infamous reputation for those in the know. Pemmican is stocked with brook trout and so attracts a few brave fishermen. The Clearwater to Rove one may have knowledgeable folks scratching their heads. There is no portage there! To get to Rove you have to go out and around through Mountain…at least today. Once upon a time, there was a marked portage to Rove on old maps. Today, that portage is the spur trail to the Clearwater campsite from the Border Route Trail. I included it for posterity since I have taken it as a canoe portage with a group of high school boys who needed tiring.

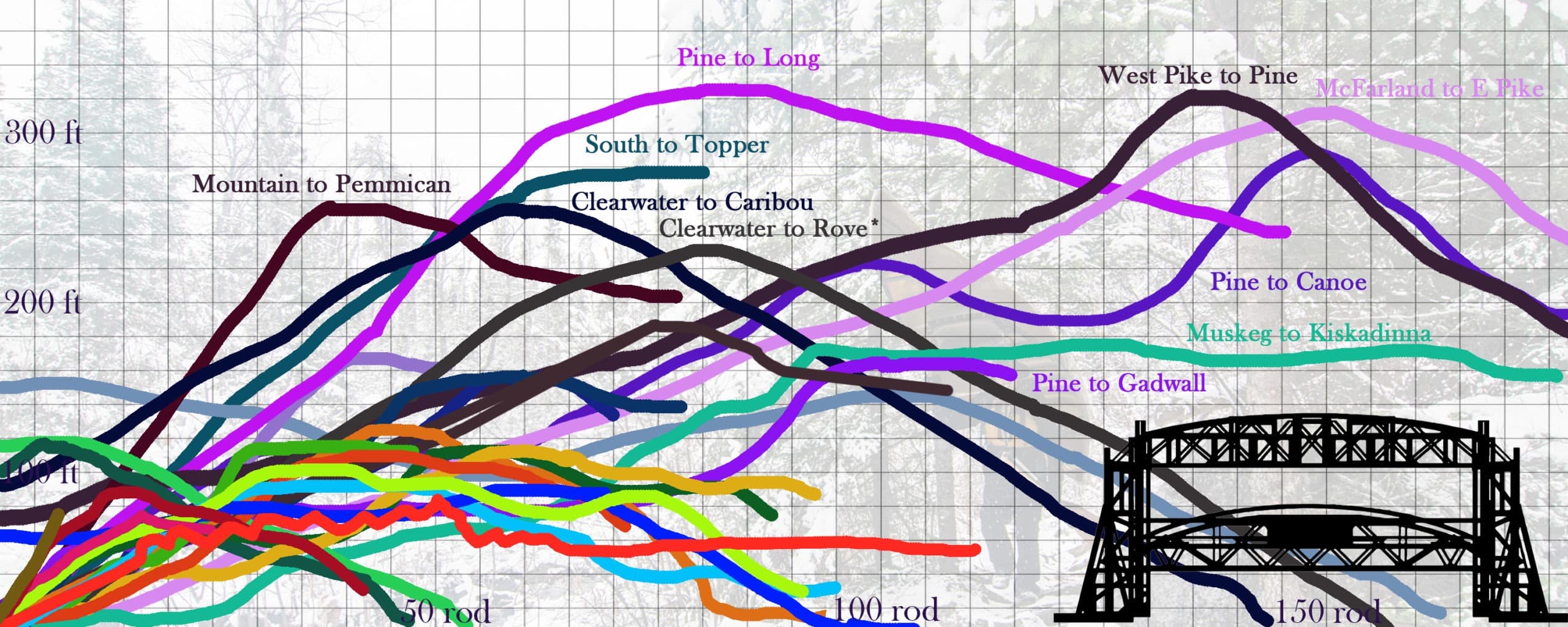

Next, we have slope. As I mentioned above, I only used the distance from the start of the portage (on its steepest side) to its peak. Most portages climb to a high point and then descend back to the water. I then, using those numbers, took rise over run and then multiplied by 100 to get a percent slope. The results are fascinating. I have long considered Mountain to Pemmican as the steepest portage in the BWCA, and it does deserve that title. From the campsite on Mountain, the portage climbs over fallen logs and through overgrown brush up 236 ft of elevation in 45 rods before coming back down slightly to Pemmican. This equates to an average of 31% slope during the time it spends climbing. Only one portage in my data truly contended with it. Over 90 miles to the west sits Takumich Lake, a deep lake sitting south of Lac La Croix. Out the south end of Takumich is a small lake with the pleasant name of Trillium. This portage, despite being only 40 rods long, gains about 70 ft of elevation in the first 15 rods putting it at about 30% slope also. There are other short portages in the BWCA which come to mind that may also come close, but, again, they are within the margin of error for maps due to their length. Another Takumich portage into Trygg also makes the top 12 steepest slopes. E Bearskin to Moon and Stairway Portage are up there (no surprise, they both have stairs.) Spaulding to Bench and Pine to Vale are both portages to stocked brook trout. As mentioned earlier, the portage to Gijikiki, Eddy Falls, Jasper to Kingfisher, South to Topper, and Hanson to Cherry are well known in their own rights. And, as usual, the rest are less well-known except for those of us who tell stories about them, and that’s the way it should be! These numbers are cool to look at, and the graphic comparing the elevation gained alongside the lift bridge adds perspective. What truly makes a portage though isn’t the numbers but the stories. The hot days with sweat pouring down as you push yourself up the final climb. The early spring trips when the landings are so flooded that you wade ashore. The early summer afternoons when the clouds of bugs fill the lungs every time you try to catch a breath and cover the arms with bites every time you reach to steady the canoe. These are the stories that stick with you that are brought up around campfires or at lunch breaks after you begrudgingly return to work. And it’s the experience of overcoming the elements and the obstacles that give a spirit of accomplishment and adventure more than any number or chart. But for those of us who proclaim themselves geeks of this special wilderness, and seek to understand it at every level we can, this is just one more tool in the belt to appreciate this place at another level.

Check out the graphics and data below! At least for me, it’s really fun to stare at the names of lakes that I recognize and remember the days I took these portages. Likewise, the remainder of this list allows me to look forward to the challenges that are still to come. The table is color-coded to the lines with the chart to compare portages side-by-side and lists the names of attached lakes in the order they appear on the map. Which of these portages do you remember?

Here the steepest portages in the BWCA are compared alongside the Aerial Lift Bridge in Duluth. The elevations are in feet, the distances are in rods. The lift bridge rods are not correct, it is simply a comparison of elevation.

[…] the burden we bear for wilderness travel. Some portages stick with us whether they are steep (see our previous article), filled with obstacles like mud, brush, or boulders, or if they are gathered close together. Other […]