Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates about new articles, great deals, and information about the activities you love and the gear that makes them possible:

Have You Read Our Other Content?

Gear Features: We’ve got your back(straps)!

At Portage North and Sundog Sport, we sell gear that we would want to use and that we can trust. In that pursuit, we are constantly improving our gear so that it can be more enjoyable to use, more trustworthy, and easier to make to a high standard. Much has changed since Portage North…

The Ten Types of BWCA Campsite

Every traveler to the BWCA has their ideal of what a campsite should look like and what features it should have. Perhaps it has a sprawling camp kitchen or a nice overlook. Perhaps it’s perched on an island or alongside a sprawling beach. But whether the campsite is easy to access or is tucked back…

In the Context of Wilderness

Earlier this week, September 3rd, was the 59th anniversary of the 1964 Wilderness Act which established the BWCAW and 53 other areas as newly defined wilderness. The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness has since gone on to become one of the most well-known and widely-beloved wilderness areas in the country. In examining the BWCAW today,…

A Bird’s Eye of the BW – Telling the Story from Above

It started as a funny game of sorts. As I was scrolling past google satellite imagery dreaming of future canoe country routes and trip plans, I would begin noticing the occasional canoe group on the photos. I soon began looking for them. It was a game of “I spy,” picking out small floating canoes and…

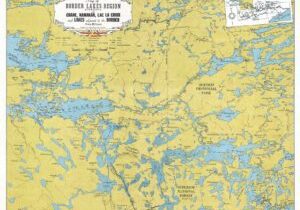

10 Lost Routes in the BWCA

Warm weather in February is a dangerous thing. If it’s too warm, the mind starts wandering ahead to summer canoe adventures. Warm weather only intensifies the time spent pouring over maps both in remembering treasured trips past and scheming the ones to come. And for me, one of the things I’m looking for on the…

Map Mondays – Week 10 – Angleworm to Wood

As part of our continuing series on the “route planning game,” we are creating routes using randomly selected entry points, exit points, and number of days to create unique and fun BWCA routes. Let’s check it out! Total Mileage: 45.5 milesNights: 5Paddle Distance: 36.7 milesPortage Distance: 8.7 miles Day 1: Miles: 7.6Target Campsite: Thunder LakeDescription:…

How to Name Over 1000 Different Lakes – The BWCA

The Boundary Waters have seemingly endless lakes bearing names from Ojibwe, French, English, or English mistranslations, misspellings, or honest translations of the Ojibwe. Many have fascinating backstories of how they came by their names. Some lakes have seemingly had the same name as long as time can remember while others have switched multiple times. This…

The Ten Most Challenging BWCA Lakes to Visit

The Boundary Water Canoe Area Wilderness encompasses over a million acres and 1100 named lakes interconnected by portages and streams, but sometimes that vast expanse can feel a little cramped, especially along entries where larger numbers of groups congregate. For the cynic who feels the BWCA is lacking some inherent quality of wilderness in this…

Map Mondays – Week 8 – South Kawishiwi to Moose Lake

As part of our continuing series on the “route planning game,” we are creating routes using randomly selected entry points, exit points, and number of days to create unique and fun BWCA routes. Let’s check it out! Total Mileage: 51 milesNights: 4Paddle Distance: 46.7 milesPortage Distance: 4.4 miles Day 1: Miles: 9.4Target Campsite: Kawishiwi River…

Map Mondays – Week 5 – Baker to Magnetic

As part of our continuing series on the “route planning game,” we are creating routes using randomly selected entry points, exit points, and number of days to create unique and fun BWCA routes. This week highlights a route across some of the busier routes on the eastern BWCA but, in using some creative strategy, allows…